Ars longa.Vita brevis.

Visual Design. It’s what I love. It’s what I’m good at. Developing a WordPress website for one client in the morning and fine tuning the kerning on signage for another in the afternoon. Here's my personal history of graphic design as I've lived it from college graduation to the present day.

1974 to 1981

When I graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1974 and began looking for a job I didn’t have a clue about graphic design. I know, I know. When people ask what I went to school for I always answer graphic design but that’s only because graphic design stands the best chance of being understood. In actuality, my BFA is in illustration. You may remember illustration: Saturday Evening Post? Norman Rockwell? No? Too young, eh? Well, that’s why I’m writing this history of graphic design as I’ve lived it through decades of remarkable change.

A few years ago I casually mentioned to a colleague of mine at the Apple store that I’d been working as a professional graphic designer for ten years before the Mac was introduced. He was incredulous. “How can you do graphic design without a computer?” he asked. I don’t blame young folks for believing that nothing existed before computers because in their lives nothing did. But the fact is that wasn’t until the ‘80s that BMW began using computers to design its cars. How did they do it? Drafting tables, baby! Same with graphic design.

Of course, as an illustrator I first set out to make a living illustrating. As it happened, though, the mid-seventies were pretty much the last gasp of illustrations in magazines and print ads, that is to say, hand-drawn and/or painted artwork. Photography had pretty much displaced “fine art” in the realm of advertising and editorial content by that time.

Which is not to say that I didn’t have some success. My work was published in several local, regional and national magazines but it soon became apparent that financially the numbers just didn’t work. The Porsche that Road & Track published netted me $50.00, chump change even in 1978 dollars considering how long the illustration took me to complete. Time for a real job.

My father had a friend at an insurance company who offered me a job, asking dismissively “Are your drawings something you want to hang your hat on?” That stung. I resolved in that moment to make my living in a field at least related to the talent that I'd spent four years in art school developing and refining.

Through my friend Bob Beaulieu I found a job at Cosco Graphics, a company that made acrylic and rubber stamps for adding logos and type to “corrugated containers,” the raw boxes that ship products to retail stores. That’s where my graphic design education really began.

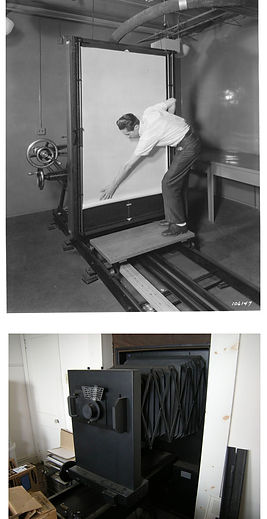

At Cosco, in addition to a drafting table, a T-square and a triangle, my chief tools were a set of Rapidograph ruling pens and a Brown vertical process camera. This beast sat half in and half out of a darkroom that was accessed through a revolving, light-proof door. Once a logo was hand drawn with a pen and filled in with brushed India ink, the “artwork” was mounted to a rack outside the darkroom. One then entered the darkroom and opened what appeared to be a huge oven door which had a vacuum that would hold a sheet of negative photo paper firmly, focused on the artwork through the lens outside the darkroom, closed the door, set the photo timer and pushed the exposure button. At the end of the exposure, one opened the door, sandwiched the negative paper with a sheet of positive and ran the pair through rollers in a tub of (no doubt toxic) chemicals.

The purpose was twofold: 1) to produce a thin piece of photo paper that could be “pasted up” with hot wax on the drafting table and 2) to change the size of the graphic, if necessary, which it usually was. Typically, a graphic would be inked many times larger than final size and reduced to 10% or 20% of the original on the stat camera. At left is a sample of a logo that I drew at 12” x 12” and reduced to postage stamp size in the darkroom (note the ink smudge!).

My next career move was to the Associated Industries of Massachusetts, a Beacon Hill lobby group. In addition to an invaluable schooling in the art of politics, my design skills took a big step forward from my windowed cubicle on the 40th floor of the Prudential Tower. It was also fun riding in the elevator with rock stars heading to the WBCN studios ten floors above us.

AIM had a small darkroom with a much more modern, compact Agfa Repromaster stat camera. Same principal though, same positive and negative paper and nasty chemicals.